We’re in the midst of our third anniversary of the date our wonderful daughter Maya died and I am thinking of the significance of ritual and remembering.

This is the third year we have piloted a course through two months of tenderness and tumult, as the gathering darkness of autumn coincides with the start of a season of remembering Maya.

Two months after she died I wrote about navigating the time between her death, at the end of October, and her birthday at the end of the year. And now, three years on, I feel that I can write something again.

This goes out as a thank you and a tribute to our friends, Maya’s friends and our family. And also it’s for anyone who knows me: as I wrote in that first essay, ‘this new, unwelcome, unwanted reality is now a part of me and perhaps it can help those who know me, work with me, love me, to understand a little of what this feels like.’

This is, in some part, an update.

Over the past three years we have been feeling our way in creating ritual and ways of marking the anniversary. So at the end of a week immersed in remembering, I hope I can bring some reflections on where we have landed, through a combination of accident and clumsy improvising. Living in a culture which doesn’t seem to have a map to help us navigate grief and death, I have had time to ponder, what I see as, a universal need for remembrance and ritual for lost loved ones.

I feel very fortunate to have a Christian faith which has given me a North Star to orient myself and some measure of steadiness through the whirlwind of loss. And it also brings a church family that cares for us, bringing giant casseroles to feed us, and our many visitors, in the weeks after Maya’s death, and praying for us faithfully over the years. But space for ritual is few and far between in the Church of Scotland, something I miss from previously being in Anglican/ Episcopal churches. Unusually for our church tradition, the service on the first anniversary of Maya’s death was part-themed around All Saints Day, a time of remembering those who have gone before, bringing many references to our collective grief for Maya, which brought great comfort.

Maya died early in the morning after a night we spent between her bedside, and in fitful bouts of half-sleep in the intensive care unit family room. We have taken to gathering with friends of Maya, and some of our friends, on the anniversary of that evening, 30th October, remembering that long vigil and our journey from hope, through the growing realisation that Maya wouldn’t make it.

The next morning dawns on the unthinkable reality that the world can carry on existing without Maya in it. Three years ago, it was the start of a dazed and otherworldly time, the weeks between her death and funeral (which I’ve written about). So we gather for the vigil, marking the evening before she died by sharing lovely food, wine, Maya’s favourite vodka, and hilarious stories. And by giving ourselves a space where we can be sad, cry if we want, and be together in our grief.

I have taken a whole week of leave on each anniversary so far. This started as a recognition that we would need the time to spend together as a family, and has evolved into a kind of ritual of its own. Seeing friends, having food together, walks, a gathering of our ceilidh band, and work-parties and bonfires in the woods. It has seemed a natural evolution of ritual, shaped by circumstance, and the time of the year. It’s the third year of it now – and surely the third time it becomes a tradition.

Tradition and ritual have become part of my thinking as I contemplate what we can do to smooth this journey of grief for ourselves, but especially for the young people involved – Maya’s friends, sister and cousins.

It has not escaped us that the anniversary of Maya’s death falls on All Hallows eve, which is also the eve of Samhain, the Celtic festival that marks the end of harvest and the start of the darker months. A time when, according to both the ancient beliefs, and the Christian All Hallowtide, which came later, that the veil between the world we know and see, and the next world grows thin, a liminal time, and people remember those who have died. In Mexico, and other places in Latin America, they take the festival very seriously with their Day of the Dead and, since Maya died I have thought a lot about festivals around the world that help people to grieve together and remember their dead.

Around the time of the first anniversary of Maya’s death my sister told me about Famadihana, the Turning of the Bones, a festival that takes place every few years in the highlands of Madagascar. She had just returned from a visit where she had passed through a village celebrating the festival (she has been working in the country and with Malagasy colleagues for the past thirty years). She described passing a procession of villagers singing, dancing and carrying the exhumed bodies of their deceased to a place where they would wrap them in new shrouds and hold festivities before re-interring them. I remember thinking how wonderful it would be to have a formal opportunity to communally acknowledge loss and share our joyful memories of loved ones who have died with the whole community. Instead, we all need to find our own ways of remembering and make our own rituals or traditions.

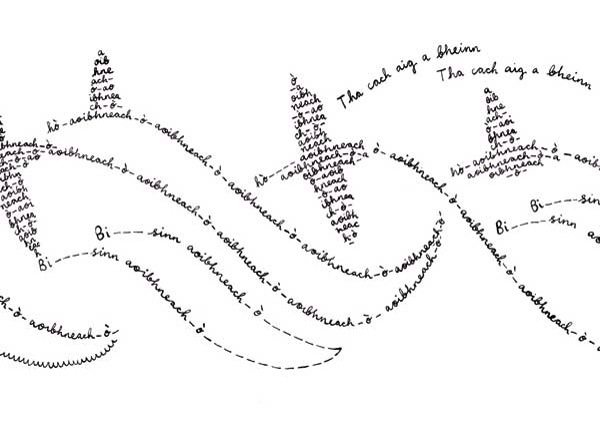

In the first year of the anniversary I took a week of annual leave and planned activities as a way of surviving the week. The plan was to walk segments of my circumnavigation of Glasgow’s Green Belt, with friends and with my husband and daughter. That week of the walk, particularly, I came across many ways that people remember and commemorate loved ones: on one walk we found a Gaelic description on a home made bench with a tiny bottle of whisky hanging on a nearby hawthorn, and on another passed a multitude of tributes and benches. The serendipity of coming across so many forms of remembrance that week, in places loved-ones evidently regularly returned to on significant dates, really helped in in navigating that first anniversary of remembering Maya.

In astronomical terms, Samhain, All Hallows, is also significant. 1st November, falls half way between the autumn equinox – where the days are of equal length, and midwinter – the shortest day. This means we are at the point that the rate of change of day length turns and starts to slow. We are no longer accelerating towards the dark, but gradually slowing to a momentary pause that will come at midwinter.

I’ve always found this time of year hard, ever since I moved to Scotland in 1997. The dark winter months, when we leave for work in the dark, and we return in the dark, crush my usually buoyant inner energy. I feel flatter, listless, pining for the boundless possibilities of the Spring.

Strangely, for me, it is the anticipation of the dark days that are worse than the experience itself. Chatting with a taxi driver one June I mentioned I was on my way home from a friends midsummer party. “Ah, the nights will be drawing in soon enough” he mused. And I was totally with him. The realisation that winter is on the way starts at midsummer, just a niggle, but it’s there, an awareness that this pure, exquisite moment cannot stay.

My antidote to the dread of the winter coming careering towards me, has been to do as much as I possibly can before midsummer – to say yes to all adventures, cramming the days from the start of April to midsummer with outdoor fun: camping, walking, parties. This year, I saw a friend just after midsummer, who expressed relief that he could, at last, rest up – he said that, since I’d told him my ‘say yes to every adventure before midsummer’ philosophy, he had taken it very seriously and was now utterly exhausted. “I’m so relieved to reach, the longest day, so I can have a rest” he said.

It makes perfect sense to me that the ancients in Scotland celebrated these in-between astronomical dates – when the rate of change of light length slows (or, at Imbolc in February, speeds up).

Since I had the realisation that 1st November is the point that the journey towards the dark starts slowing, it has brought a strange comfort. Things aren’t getting better yet, but they’re not getting worse so fast. And that is, perhaps, as much comfort as we need. I don’t know whether this is a parable for our times – but it seems like an important moment to mark as we head into the winter.

In writing this, it dawns on me that this could also explain why I find August brings on the dread of the winter in force. It’s counter intuitive as the days are still long and the weather can be balmy and beautiful. Winter is months away. But it is the time when light is being lost increasingly rapidly. It’s when I start thinking about the anniversary of Maya’s death, Christmas and her Birthday, a hard season to spend in the dark. And it’s when I need to start planning.

It’s only this year that I have realised how much these things are connected, and to see how our ways of remembering Maya have become part of a seasonal celebration. ‘Maya Week’, as I have decided to call it (having, this year, declared it a tradition), starts the weekend when the clocks go back and ends the Sunday after Allhallows.

In a bookend to this season of remembering Maya, we have a party on her Birthday, a week after the shortest day. The first year, two months after she died, we didn’t know where we were going, but a party for her 20th birthday seemed like the only thing to do. We planted a magnolia outside our house in the rain, each of us holding onto a circle red woolen thread, a friend led us in prayer and poetry. And we huddled inside to dry out and eat a meal friends had made. It has continued each year, with planting oaks in the wood, and brings together young people and our friends in equal number.

We have held a party in early May since we moved here, when the bluebells come out in woods behind our house. It has become a time to gather to celebrate the exquisite joys of Spring, and also for our friends and Maya’s friends to take the walk to her bench up in the woods, and sit for awhile, overlooking a sea of bluebells and flanked by two huge beech trees.

Maya loved parties and people (and so do I) so this seems like the best way to remember her and celebrate her, and to bring people across generations together – Maya’s friends, her sister’s friends, our family and friends.

So what does this mean for my thinking about marking grief, remembering and ritual? We have found that having a ritual of remembering helps because it is so hard to allow grief come to the fore and to truly acknowledge what we have lost, recognising that Maya is gone. I don’t like being sad. But it is good to be sad sometimes, because something very sad has happened. The way I have found to do this is to contain it within a structure of time and space. Being with others who love Maya and feel the same helps us do this, even if we don’t talk so much about the depths of our loss, but instead share our funny happy memories, laugh together and share hilarious stories. It is two sides of the coin, one easy and joyful the other difficult and painful. But if we can bring them together at this time of year, and share it with others, it makes it easier.

I look back from the vantage point of the end of Maya Week with happy memories of communal activities: a huge bonfire clearing the brash of a whole year of gardening and woodland management, a mini ceilidh in the living room, feasting, laughing, saunas, autumn walks, (watching Celebrity Traitors, talking about Celebrity Traitors), and a weekend in the Caledonian pines of the Cairngorms. And, thanks to a friend of our younger daughter, inter-generational yoga crammed into a sitting room cleared of furniture.

All of this was done with friends and family and Maya’s friends (who are becoming family). And we have Maya’s birthday to plan for after Christmas, and the Bluebell party for the start of May. Perhaps we should listen to our Celtic forebears and add a party to the calendar in August as well.

Acknowledgements:

So many thanks go out to all our friends, family, Maya’s wonderful friends, and the friends of our incredible younger daughter for all the support for the three of us. And most of all thanks to my amazing husband and younger daughter. We will keep partying on: in memory of Maya, and just because we like it.

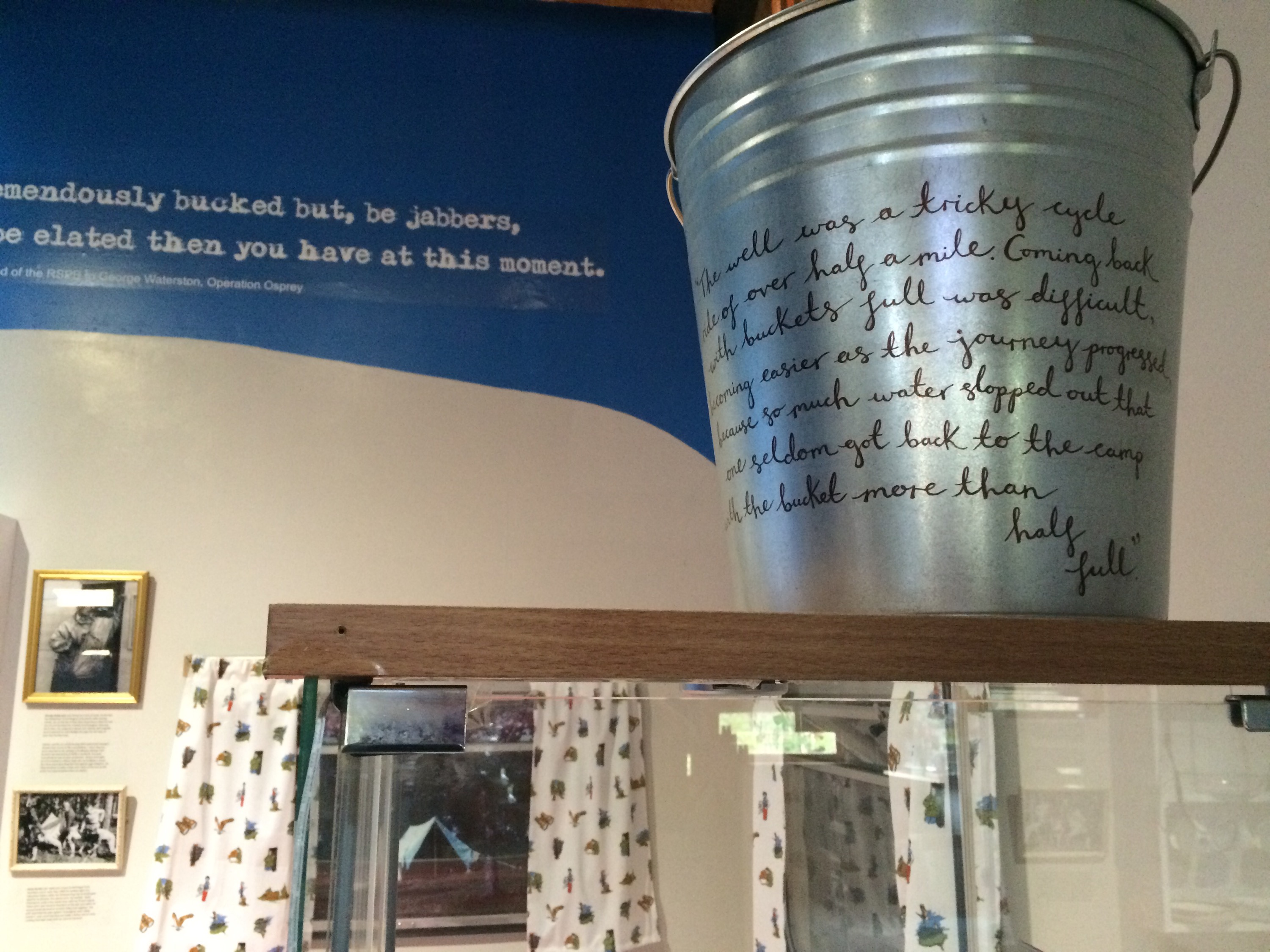

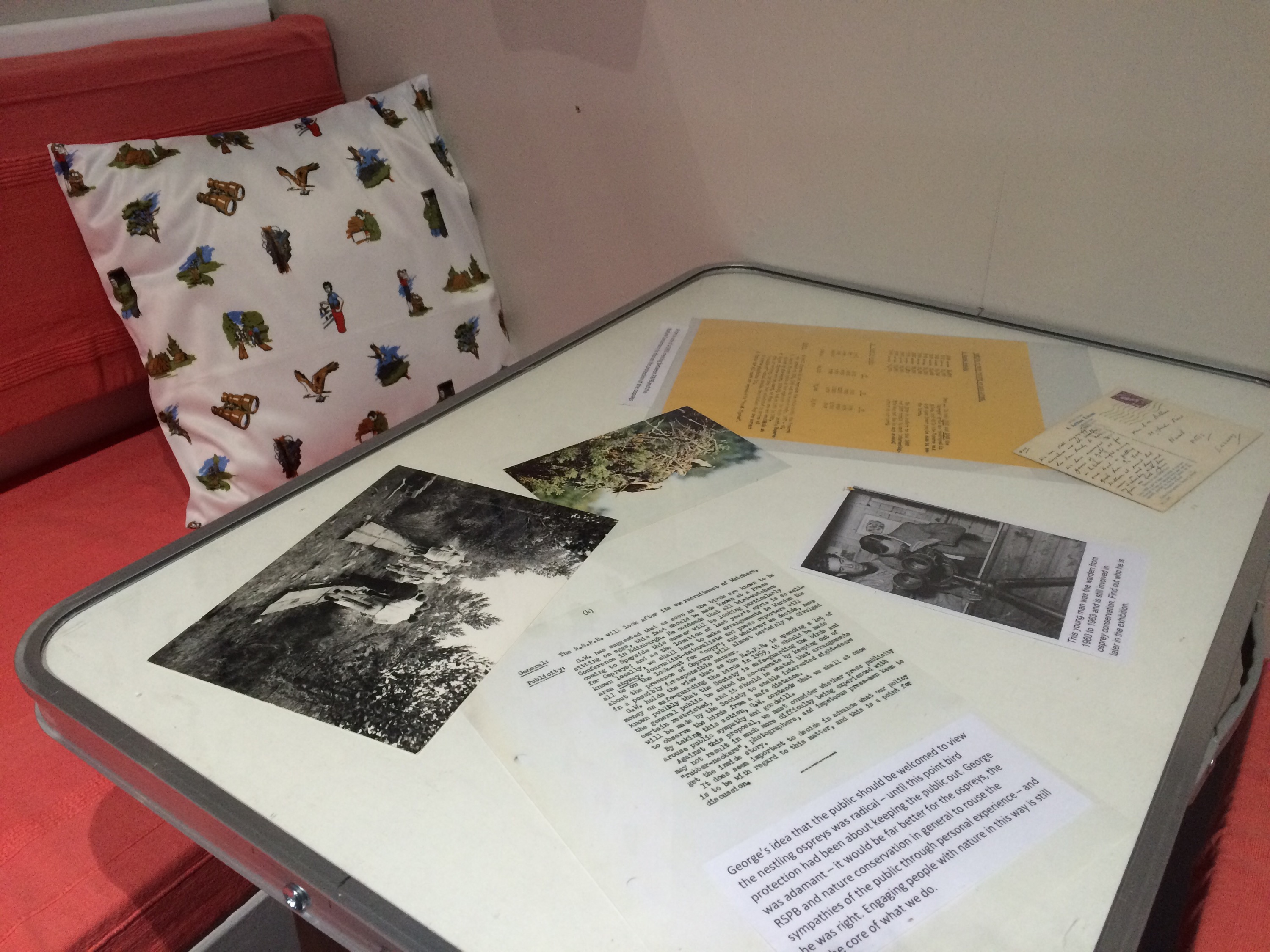

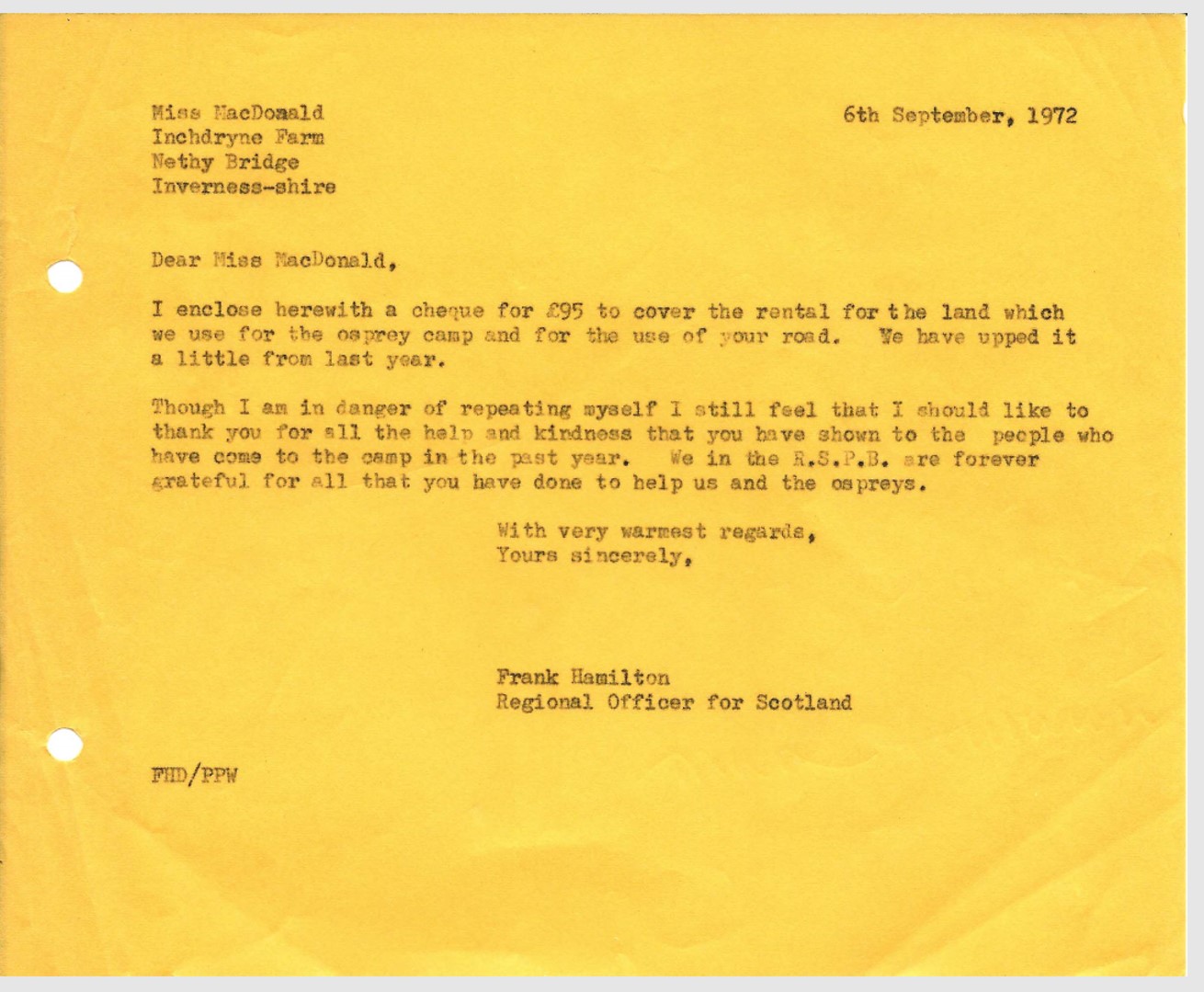

So I got started at creating the set and layout for the exhibition and went out trawling the best of Glasgow’s ample junk shops. I wanted the set to look like the inside of the 1950s caravans of Operation Osprey – a white gloss-painted chest of drawers would contain the documents under Perspex, and vintage photo frames would house the photos of our heroes. And, in my mind’s eye I saw the kind of material you would see in a 1950s kitchen on an Operation Osprey theme. It would be sewn into twee cushion covers and curtains for the caravan windows.

So I got started at creating the set and layout for the exhibition and went out trawling the best of Glasgow’s ample junk shops. I wanted the set to look like the inside of the 1950s caravans of Operation Osprey – a white gloss-painted chest of drawers would contain the documents under Perspex, and vintage photo frames would house the photos of our heroes. And, in my mind’s eye I saw the kind of material you would see in a 1950s kitchen on an Operation Osprey theme. It would be sewn into twee cushion covers and curtains for the caravan windows.

But this wasn’t really much fun. The rant really didn’t stand up to the rigors of argument, which didn’t go down well. It just caused the offensiveometer to be turned up a notch.

But this wasn’t really much fun. The rant really didn’t stand up to the rigors of argument, which didn’t go down well. It just caused the offensiveometer to be turned up a notch.

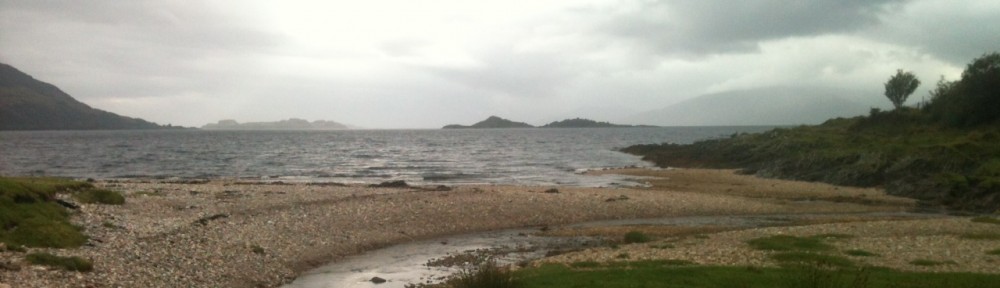

Highlands are wild, and untamed there isn’t always a bridge to hand, even on marked paths. This isn’t strictly something that I love about the West Highlands, but I crossed a freezing and rocky mountain burn today, in bare feet to keep my boots and socks dry. It was very sore and there were patches of snow on the ground, and I am proud of it, so I thought I’d put it in….

Highlands are wild, and untamed there isn’t always a bridge to hand, even on marked paths. This isn’t strictly something that I love about the West Highlands, but I crossed a freezing and rocky mountain burn today, in bare feet to keep my boots and socks dry. It was very sore and there were patches of snow on the ground, and I am proud of it, so I thought I’d put it in….