You know the feeling when something turned out really well and you can’t stop thinking about it? Something where all the hard-work and moments when it nearly didn’t happen were worth it. And where, in the end, after a huge amount of team work and a couple of late nights, it all comes together and is simply amazing. And then you can’t stop feeling maternal and proud and saying to people ‘Have you seen this thing? It’s my baby and it’s amazing’.

I hope I haven’t built it up too much, but that’s just how I feel about the 60th Anniversary Exhibition at Loch Garten to celebrate the pioneering work of Operation Osprey.

We had a tiny budget of £5000, which shrank further to £3000 once other essential items for the reserve had been purchased. Although Loch Garten isn’t strictly within my geographical area of work, as I cover the Southern and Western parts of Scotland, I’d offered assistance to a stretched team, and I had ideas. IDEAS!

While I was writing the interpretation plan for the reserve I was simply gripped by the stories from the early years of Operation Osprey: intrigue and mystery, goodies vs baddies, true heroes of conservation, boys’ own adventures and a military operation to protect the ospreys.

And the nostalgia, the NOSTALGIA…..…those photos of the camp from the 1950s and 60s where they lived in and the caravans in which the ‘cook-caterers’ rustled up three hot meals a day (majoring on mince and tatties) for the watchers. This was an exhibition just begging for the retro/vintage touch. And how better to create something with a miniscule budget than to be scouring Glasgow’s numerous junk-shops and the famous Barras in search of vintage bits and pieces to create the exhibition. This was definitely a job for me.

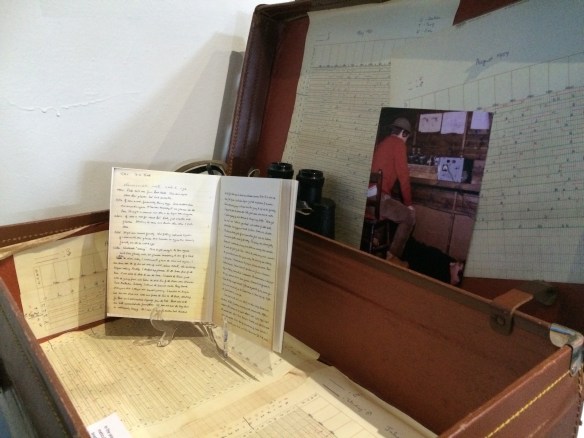

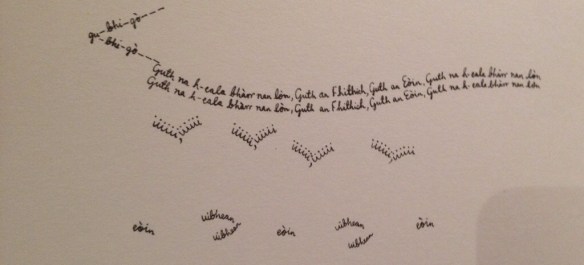

But before we could make an exhibition we needed the content – there was an archive of stuff at The Lodge (RSPB HQ) but we knew that they would be reticent to lend it to us. We needed an ambassador who could read the whole archive, sort the wheat from the chaff and advise on the key documents and objects that we needed for our exhibition. But who on earth would have the time and inclination to do a task like this? Enter Alice Shaell, a volunteer who had already gifted me her professional time as an ‘information architect’ to write interpretation for Loch Lomond. Alice became my ‘specialist volunteer’ and got started on the archive. She went to the Lodge and painstakingly transcribed key passages from the log-books, roping in her mother as an expert in 1950s spidery handwriting, and read everything they held at the Lodge.

We knew what we needed for the exhibition but it proved too difficult get them to Loch Garten safely and we were stumped. What on earth were we going to do? An exhibition isn’t an exhibition without original artefacts to link the viewer with the past.

I found out you could still buy curtain wire. And it comes out of the same tin it did in the 1950s….

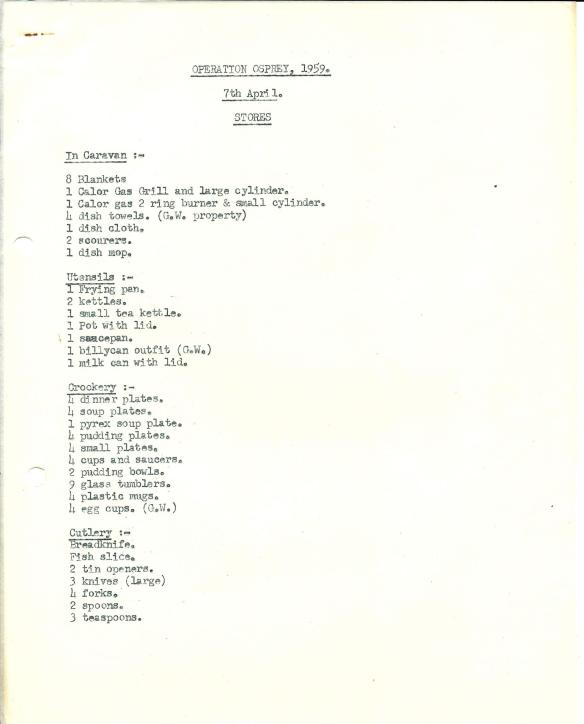

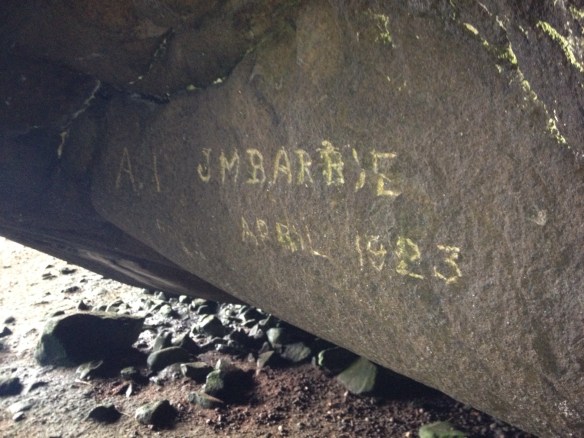

We couriered the box to Alice and she read the lot. She found that most of the documents that were in the Lodge archive had an equivalent in our box and so the exhibition started to take shape. The stories of the heroes (the stories of the women needed a bit more research and digging), the letters and job adverts, the candid (and non HR compliant) comments about the quality of the volunteers, and the need for bikes without cross-bars, George Waterston’s planning documents for the 1959 season, and, most significantly, George’s report from that 1959 season when Ospreys bred successfully for the first time.

We couriered the box to Alice and she read the lot. She found that most of the documents that were in the Lodge archive had an equivalent in our box and so the exhibition started to take shape. The stories of the heroes (the stories of the women needed a bit more research and digging), the letters and job adverts, the candid (and non HR compliant) comments about the quality of the volunteers, and the need for bikes without cross-bars, George Waterston’s planning documents for the 1959 season, and, most significantly, George’s report from that 1959 season when Ospreys bred successfully for the first time.

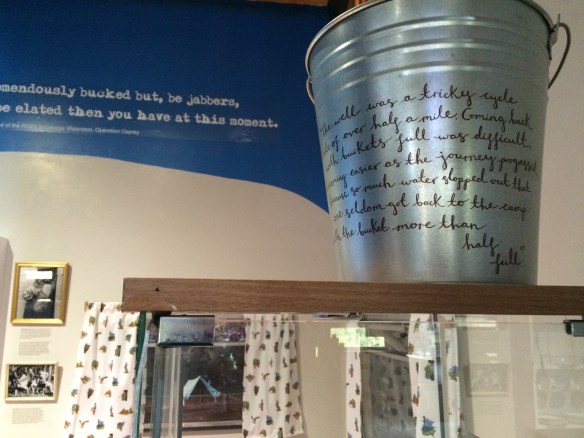

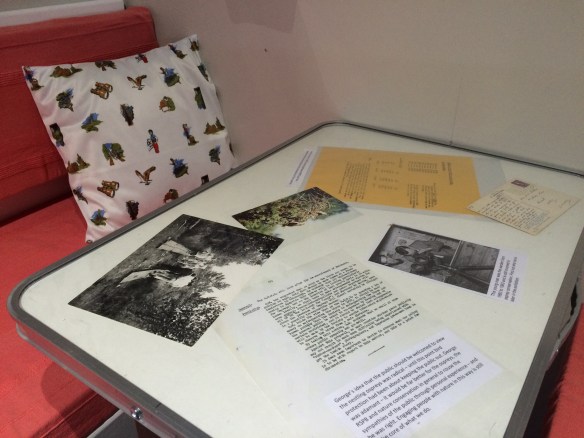

So I got started at creating the set and layout for the exhibition and went out trawling the best of Glasgow’s ample junk shops. I wanted the set to look like the inside of the 1950s caravans of Operation Osprey – a white gloss-painted chest of drawers would contain the documents under Perspex, and vintage photo frames would house the photos of our heroes. And, in my mind’s eye I saw the kind of material you would see in a 1950s kitchen on an Operation Osprey theme. It would be sewn into twee cushion covers and curtains for the caravan windows.

So I got started at creating the set and layout for the exhibition and went out trawling the best of Glasgow’s ample junk shops. I wanted the set to look like the inside of the 1950s caravans of Operation Osprey – a white gloss-painted chest of drawers would contain the documents under Perspex, and vintage photo frames would house the photos of our heroes. And, in my mind’s eye I saw the kind of material you would see in a 1950s kitchen on an Operation Osprey theme. It would be sewn into twee cushion covers and curtains for the caravan windows.

My original thought that we’d be able to get an original caravan interior and use for the set was dashed pretty quickly but Jess, from Loch Garten, mustered a team of incredibly talented volunteers who created the bench seats in plywood and painted the chest of drawers.

After an intense two days of installation, with further sterling work from expert volunteers (and a late night on a sewing machine by a very kind brand-new member of staff from Cairngorms Connect going WAY beyond the call of duty) we got it done. And here it is, Please do try and get down to Loch Garten to see it if you can, it will be there until September.

After an intense two days of installation, with further sterling work from expert volunteers (and a late night on a sewing machine by a very kind brand-new member of staff from Cairngorms Connect going WAY beyond the call of duty) we got it done. And here it is, Please do try and get down to Loch Garten to see it if you can, it will be there until September.