In preparing the exhibition to celebrate the 60th Anniversary of Operation Osprey, one of the most rewarding things has been uncovering the stories of the women involved. Women were in camp from the very beginning but their voices are, more or less, absent in the archive and accounts of the early days.

The first thing I read to get acquainted with the story of Operation Osprey was the 1971 account of the return of the Osprey to the UK by Philip Brown. Two names emerged immediately as important: Betty Garden, a camp stalwart, and Isabella MacDonald, to whom the book is so charmingly dedicated.

“Miss MacDonald was a remarkable lady who foster-mothered scores of lucky children, yet still found the time to welcome so many of us who watched over the ospreys, with apparently inexhaustible kindness and a quiet encouragement that gave many of us renewed faith, strength and enthusiasm when the fates were against us”

I was intrigued, especially by Isabella as, despite this dedication, she doesn’t appear within the pages of the book apart from a passing mention. Isabella was the crofter of Inchdryne who gave Operation Osprey Base camp its home in 1959, hosting them until the mid 1980s, and her hospitality is a central part of the story.

My partner in crime in researching the stories for the exhibition, Alice Shaell, who kindly gave a great deal of her professional time in a voluntary capacity, found some correspondence relating to the constant battle to persuade Miss MacDonald to accept some payment for her hospitality. The letters show how much respect and affection those at Operation Osprey held her in, and how grateful they were of the kindness she showed towards them.

Alice and I went to visit Isabella’s niece, who now crofts the land at Inchdryne, and was still a teenager when George Waterston set up Operation Osprey. Marina Dennis is an impressive woman, having a lifetime in crofting, journalism and public service behind her, including twelve years as a Commissioner at the Crofters Commission. Still an active crofter, and young for her age, she writes a column for the local paper and is still involved in an advisory capacity in a myriad of things. Marina welcomed us into her warm, spacious bungalow and we sat by large windows looking over her croft, towards Abernethy Forest.

Marina told us that this land had been crofted by her family since they were cleared from the Braes of Castle Grant in 1809. What is now a patchwork of fields set within birch woodland and Caledonian pine was, back then, a boggy forest where Marina’s forebears would have had to clear the land, build a house, and start to create a new life for themselves.

We started by referring to her aunt as Isabel, as she is named in Brown’s book, and were immediately corrected. “She was Bella. Everyone knew her as Bella” said Marina. Isabella [pronounced Eye-sa-bella] had been a common name in the area, there was an Isa, an Isabella and she was Bella. Marina took down a photo of her Aunt from the wall to show us. Bella, white hair swept back into in a black beret and wearing a navy dungarees was sitting on a grey Fergie tractor. A boy of around 15 sits on the plough behind. Marina explained to us that was Billy, one of Bella’s foster children.

Miss MacDonald fostered around 40 children over the years, most of which came from Edinburgh and Glasgow. “She always took boys, as she thought girls were too much of a handful” said Marina; and, as the mother of two teenage girls, I nodded vigorously in agreement. Almost all of the children stayed with Bella until they had finished their schooling and many stayed on in the area, including Billy.

She went on to tell us about how her aunt and George had hit it off as soon as they met, “The osprey nest that first year was on the common grazings” she said waving her hand towards the wet grassland dotted with trees a few hundred metres behind her home. The team had set up watches in a rough hessian tent on the common grazings in 1958. The account of the nest-raid from the logbook inventively describes the ground as, “a bog that was very boggy”.

“George was very good with local people” said Marina, “he really understood indigenous communities, and people round here liked him. It was the same on Fair Isle” she added. George had set up Fair Isle Bird Observatory after the war, a decade before he started Operation Osprey.

When George was looking for a spot for Operation Osprey base-camp Bella offered a site not far from her house at Inchdryne “It really was the spark between George and Bella that ignited Operation Osprey” said Marina. George had asked whether she could host base-camp and she said yes. “It was Highland hospitality, she didn’t do it for payment or any gain. It’s just how Highlanders are.” And it seems from all the accounts of Bella from the archive that this hospitality was far more than offering a place to pitch camp, park caravans, and the all-important water supply; it was hospitality in the fullest sense of the word, offering volunteers and staff at Operation Osprey a kindness and open-hearted welcome that came from her extraordinary generosity of spirit.

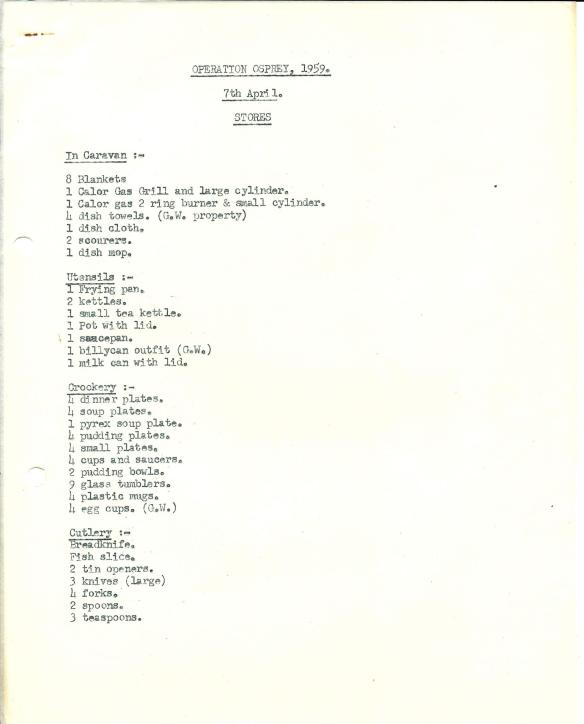

When we left, Marina directed us to the spot Bella had allowed Operation Osprey to use for all those years. In that quiet glade among the pines I imagined the bustle of base camp; caravans, canvas tents, phone lines and George’s famous Dormobile, and I thought of Bella MacDonald’s immeasurable contribution to the project and what a truly remarkable woman she must have been.